This section is a short digression into the history of the study of indigenous cartography and toponymy of the indigenous peoples of Northern Russia and Siberia.

Interest in indigenous maps and place-names in the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Russian North and Siberia arose during the period in which the northern territories were first being studied with a view to better exploit local natural resources and means of communication in the interests of the state, as well as to investigate the possibilities for settling the distant fringes of the empire. An important role was played in this effort by the Russian Academy of Sciences, which financed expeditions, including ethnographic ones, to Siberia and the Arctic. Scientists and travellers often used the maps of their guides, recruited from among the indigenous peoples of the North. Some of these maps were later brought back to Saint Petersburg, where they were studied and published by Bruno Fridrikhovich Adler (1910) in his synthetical work on the cartography of the indigenous peoples of the world. Adler also made use of materials found in scientific archives, museums and ethnographic collections that his colleagues had brought back from expeditions in Siberia. A number of birch bark and paper maps were passed on to Adler by such scientists as I.P. Tolmachyov, Ye.P. Ostrovskikh, V.I. Anuchin and V.I. Jochelson.

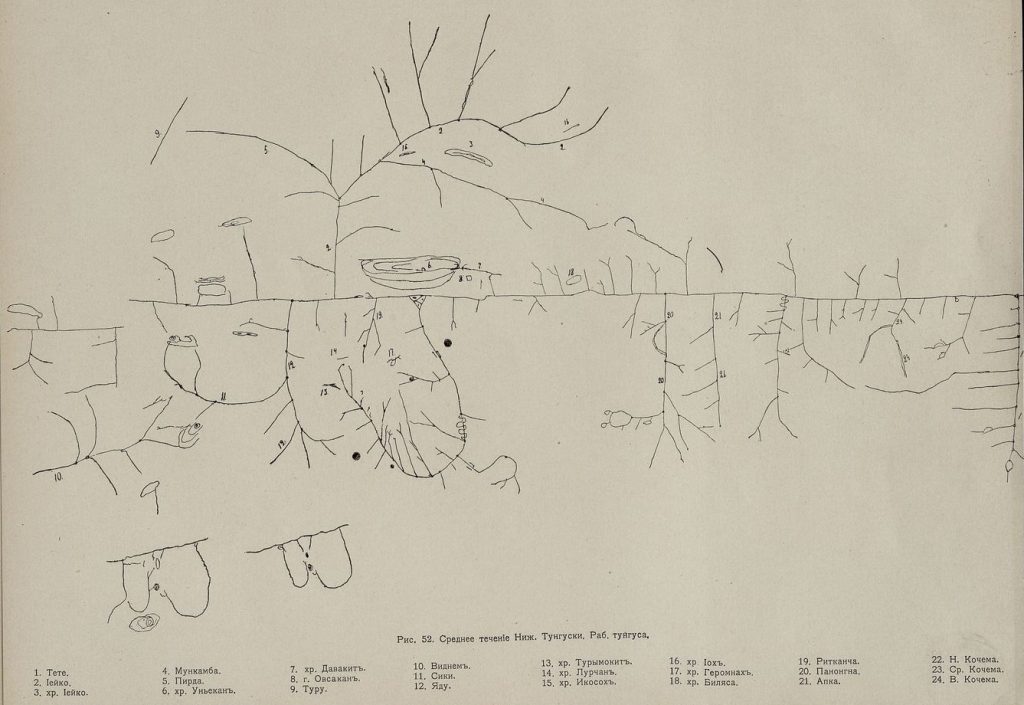

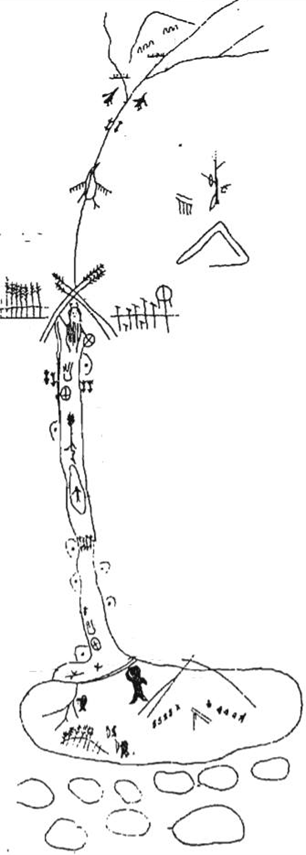

The greater part of the maps (23 in number) published in his book had been obtained from the Ewenki people (otherwise known as the Tungus) (see Figure 1). Examining the accounts of colleagues who had been on ethnographic expeditions in Siberia, Adler noted that the mapmakers of the indigenous peoples of the North had never, as a rule, seen geographical maps before – a fact which did not prevent them from producing very accurate drawings of their local areas. I.P. Tolmachyov describes the process of drafting a map as follows:

“Initially, the Tungus had drawn right onto the snow. It was only later that Messrs Vasilyev, Tolmachyov and Backlund decided to use the drawings of the inorodtsy [non-Russians/natives] for their map and began to supply their guides – Tungus, Yakuts, Samoyeds, etc. – with pencils and paper at their campsites, that they might learn from them the route of the following day. In most instances the work was carried out in tents by the light of a stearin candle. A greasy board served as the writing desk, on which the Tungus would usually prepare their food and which served as a table during mealtimes […]. When drawing, the Tungus would orientate the map not to the cardinal points, but in conformity to the direction of the main water artery and its position in relation to the author at the time of drawing. They mostly orientate by rivers and lakes, and less often by the mountains, dwelling places, rock outcrops (of white and black stones), snow ridges, the inclination of forest vegetation, etc. They did not mark the paths followed by human beings, or even forests, on the map at all, and in general they rarely used these to orientate themselves.” (Adler 1910: 100)

Fig. 1. An Ewenki map of the middle reaches of the Lower Tunguska (Adler 1910: 120).

The unique spatial and temporal perspective of the geographical knowledge of the Ewenki and other related Tunguso-Manchurian peoples was noted by the ethnographer and linguist Sergei Mikhailovich Shirokogoroff (1935: 66), who compared their mapmaking principles with those of railway timetables, and the Ewenki themselves with professional topographers. In the Soviet period of Russian ethnography, the study of Ewenki hydrological maps and geographical terminology was continued by Glafira Makaryevna Vasilevich (1963). Her study is, perhaps, the only such long-term and extensive cartographic project of its time aimed at the systematic collection of cartographic materials among the community under study. Her extensive archive of Ewenki maps, now kept in the scientific archive of the MAE RAS, is of great value to both scholars and members of indigenous peoples themselves. Vasilevich was also the first researcher to pay special attention to Ewenki place-names, their structure and functions. All her maps contain the names of rivers (hydronyms) in the local Ewenki dialect, and were plotted both by the researcher herself and by her informants. The uniqueness of these hydronyms lies in their great semantic diversity: out of more than 1,500 names, half constitute either a new concept or a new combination of toponym and affix.

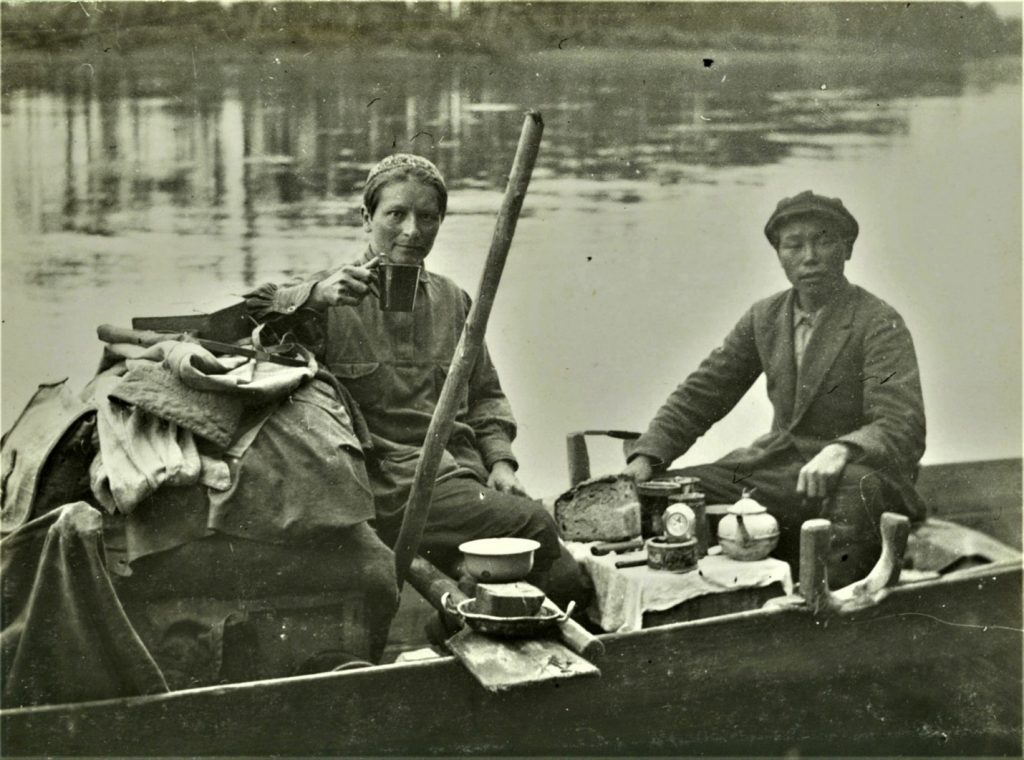

Photograph: G.M. Vasilevich (left) on an expedition to the Vitim-Olekma Ewenki, 1929. Source: National Library of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

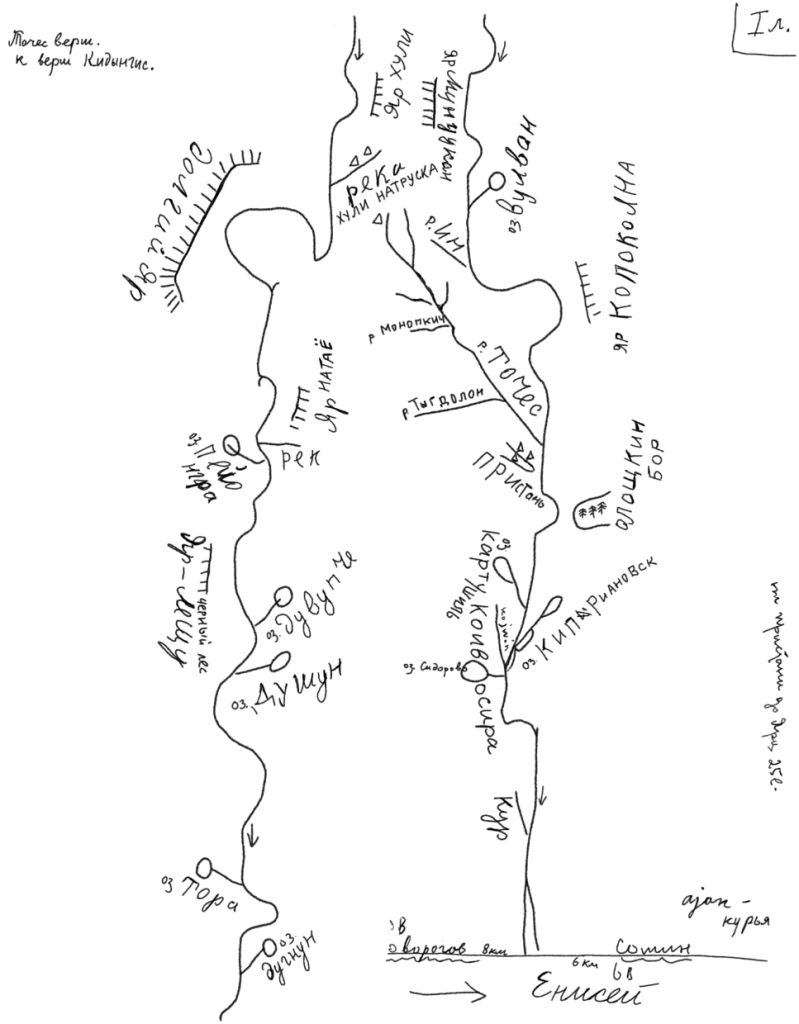

Vasilevich describes the process of sketching a map thus: “The draftsmen, of course, did not orient their drawings to the cardinal points, but they gave the main directions of the flow of large rivers correctly. Usually, before starting, the Ewenki would sit for a long time, turning over the sheet of paper, until, finally, he stopped at a certain point on it, and began drawing the main river leading way from himself downstream, adding all the tributaries along the way. Where tributaries of other rivers were found between the upper parts of the tributaries, these were added too. Mountain ranges were marked with straight lines or short hatching” (Vasilevich 1963: 318). In addition to rivers, lakes and hills, the Ewenkis would often depict yary or steep banks on their maps – outcrops formed where riverside beach ridges or levees rose up, covered with pine forest (cedars and mixed species woodland). Such yary may be seen on the map Vasilevich obtained from the River Sym Ewenkis (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. A redrawn fragment of a hand-drawn map of the Yenisei river system (MAE RAS, collection Vasilevich 22, inventory 2, file 75, sheet 6).

It should be noted that all the above-mentioned maps were drawn by the Ewenki on the urging of researchers. The question therefore arises: is it possible in such a case to call these maps indigenous at all? We are of the opinion that they can be attributed to indigenous cartography, since the Ewenkis, like other peoples of the North, occasionally drew such route maps to explain the way somewhere or leave a note about their movements with other members of their group. However, it had been impossible to preserve these maps, and indeed unnecessary, since they did not represent any long-term value to their creators.

An example of a unique cartographic tradition in Siberia is given by the Yukagir tos, systematized and published in the work of N.B. Vakhtin (2021). Tosy are a form of birch bark writing (from the Yukagir shangar shorile – “writing on the skin of a tree”). Vakhtin notes that their main function was the transmission of information, including spatial information, in graphic form. Tosy were divided into two types: “male” and “female”. A “male” tos would constitute a map of the area and the routes taken, left behind by Yukagirs for those belonging to the same group (Figure 3). “Female” tosy are love notes from unmarried girls to young men. For the purposes of this overview, we are interested in the “male” tosy, that is, area maps. B.F. Adler cites in his work several similar Yukagir maps, collected and given to him by Jochelson. At the same time, Adler (1910) notes that, in addition to drawings on birch bark, he knew of one Yukagir letter carved on a stick, which he had received from K.A. Vollosovich, who had been working among the coastal Yukagirs. The drawing in question depicts a direction and a river, beside which a certain event had taken place that the draftsman had wanted to tell somebody about. Like Adler, Vakhtin draws attention to the striking similarity between the Yukagir tos and the maps of some groups of North American Indians.

Fig. 3. A tos, depicting Yukagirs leaving their village on the River Korkodon for spring hunting on the snow crust (Jochelson 1898).

Another peculiar feature of the tos is that it can not only convey a static map of an area, but also events, everyday life, and movement through space.

An interesting example of this kind of map is a Chukchi map made on seal skin, kept in the ethnographic collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University (Figure 4). It was supposedly obtained in the 19th century by the captain of a whaling ship in the Bering Strait. On this map are scenes of hunting and fishing, various animals, individual landscape features, settlements, Chukchi engaged in economic activities, and even a European ship. The purpose of the map, however, remains unknown.

Fig. 4. A Chukchi map from the collection of the Pitt Rivers ethnographic museum at Oxford University

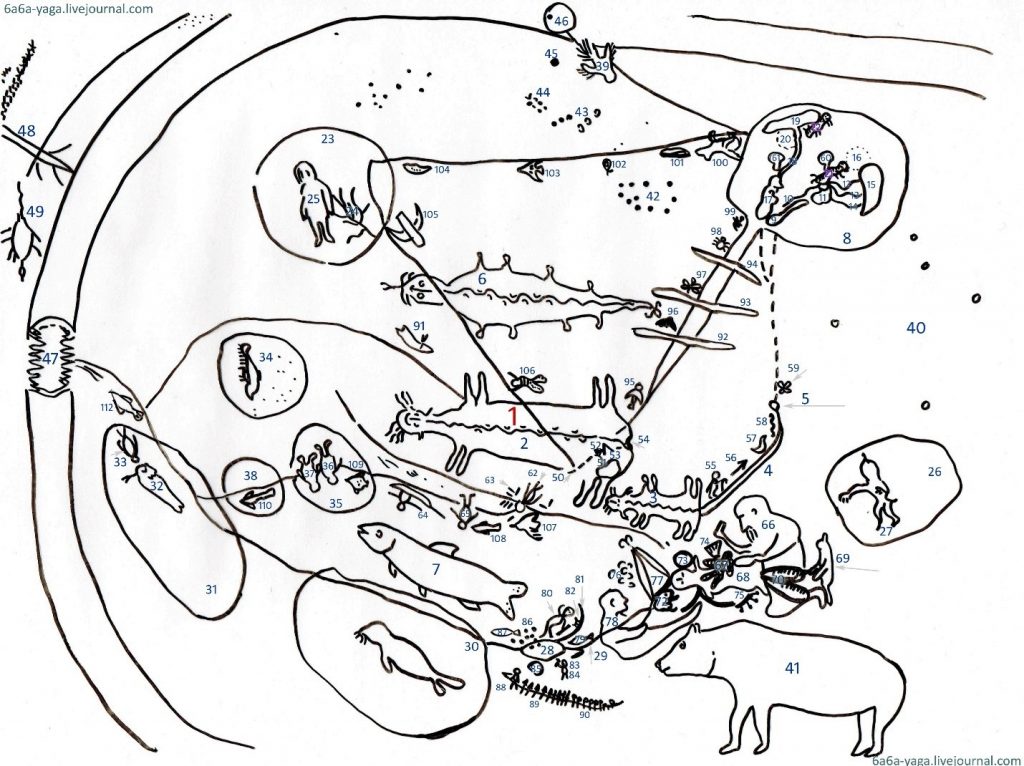

A large portion of indigenous cartography is comprised of cosmological, celestial and shamanic maps, as described in the work of Ye.A. Okladnikova (1998). Drawings on shamanic drums, representing a map of the universe and/or the routes followed by shamans, can serve as an example of such maps. The researcher notes that in some cases, shamans’ costumes can be regarded as a map of the journey to non-human worlds. By way of example, Okladnikova (1998: 333) cites the costume of an Ewenki shaman from Yakutia, on which specific topographical information is depicted: the red stripes on the costume indicate places with a fire, for instance, while green indicates lush greenery, and blue is marshy areas or those scorched by fire. The sequence the stripes are placed in is of no less importance: each is equivalent to one day’s travel, and the spaces between the stripes indicate turns on the path where the shaman passes around the obstacles encountered. Travels to the shamanic realms and mental maps of the regions moved through during rituals could be transmitted by means of narratives, through which the listeners followed the sequence of places the shaman passes on his way. Some ethnographers working with shamans specifically asked them to sketch out the structure of the shamanic worlds. One example of such maps is the Oroch cosmological map, obtained in 1929 by V.A. Avrorin and I.I. Kozminsky from the shaman Savely Khutunka in the village of Khutu-Data on the River Tumnin. Here is how the researchers described the process of creating this map:

“On a large sheet of writing paper measuring 109 x 70 cm, over the course of 3-4 days, the ‘map’ of interest to us was drawn with a simple pencil. In total, at least 15-20 hours were spent on this work, and on the first evening the shaman himself did the drawing, but then decided that the results of his efforts weren’t ‘beautiful’ enough, and so he got two young Oroches to do the rest of the work. Savely himself and his ‘artists’ worked with extraordinary enthusiasm. The work on the ‘map’ attracted the entire male population of the small camp to Savely’s tree-bark dwelling. Critical remarks and advice from the Oroches present gave the work the character of a collective creative activity, in which the first and last word always belonged to the old shaman.”

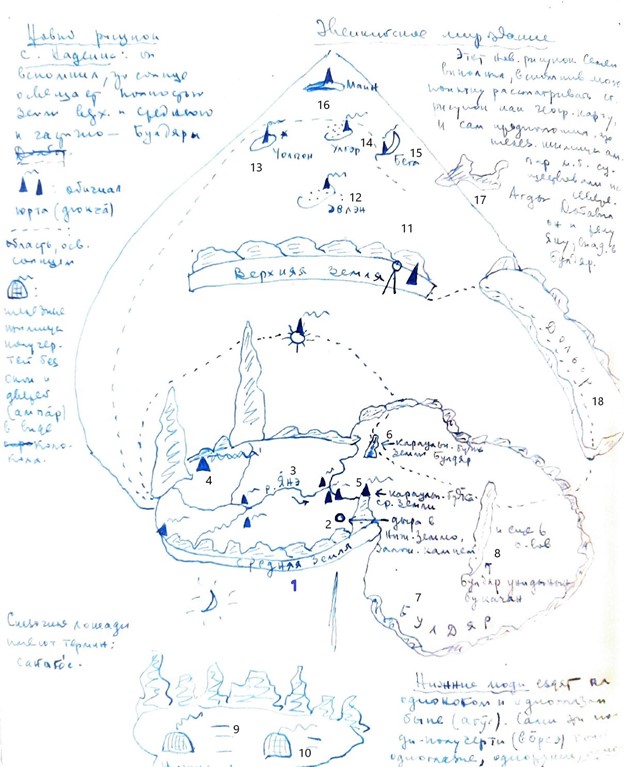

The researchers redrew the resultant map, labelling it with numbers (Figure 5). Europe and Asia are placed in the centre of the map (numbers 1 and 2), on top is America (6) in the form of a horned dragon, and on the bottom Sakhalin (7) in the form of a salmon. Shown on the map are the entrances to the non-human worlds inhabited by spirits and various beings, such as the tiger half of the moon, on which the old mistress of tigers lives (22), as well as the constellations, seas and rivers. Below is a detailed topography of the Oroch universe.

Fig. 5. Map of the universe by the Oroch shaman Savely Khutunka, 1929. Redrawn map from the LiveJournal account 6a6a-yaga.

Topographical description: expand “In the centre of the ‘map’ is drawn our continent – 1 (Europe and Asia), which for the Oroch takes the form of an eight-legged antlerless moose with a large and luxuriant moustache facing towards the south, shown flattened on the map for convenience. Its backbone – 2 – is a mountain range consisting of nine peaks. This ridge divides our world into two equal parts: east and west. On the eastern half of the world live the Oroch and their closest relatives and immediate neighbours. The Russians and all other peoples live in the western half. China is located on the moose’s head. As the Oroch have it, this uneven distribution of population over the earth was something that had come about in relatively recent times. Previously, the Oroch, as they say, had been so great in number that flocks of swans flying over them were turned completely black from the smoke of their fires. Our forests are the moose’s hair, the animals are its parasites, and the birds are midges and mosquitoes hovering over it. Sometimes the moose tires of standing still, and shifts from foot to foot, resulting in earthquakes. A huge bear lives in our world, which is the earthly master of all game animals. For purely technical reasons, it is depicted not on the earth, but in the lower righthand corner of the ‘map’ – 41. Right underneath the moose that depicts the earth is a second moose, exactly the same as the first – 3. This is the world of the dead. On the ‘map’, the second moose is drawn, again for purely technical reasons, somewhat lower and to the right of the first one, albeit in a significantly reduced form in comparison. The world of the dead is almost always dark; it is only light when the sun, revolving around the earth, passes along the side of both mooses and with its oblique rays briefly and dimly illuminates the back of the lower beast. The world of the dead is an exact copy of this world, or rather, a kind of mirror image and negative reflection of it. Everything there is the opposite of how it is here: once an old man reaches the world of the dead, he turns into a child; a child into an old man, a smart one into a stupid one, a lucky one into a failure, a merry fellow into a gloomy sceptic, a whole thing into a broken, smashed or torn thing, a good thing into bad, and vice versa. One consequence of this concept of the afterlife is that the Oroch, when burying the dead, put clothes in the coffin that have been specially torn, with smashed vessels and broken hunting equipment. A river – 4 – comes up against the croupe of the lower moose at its mouth, leading to the upper world beyond the clouds. The upper reaches of this river abut an opening – 5 – in some kind of inner (small) celestial sphere, leading to the upper world. To the west of our continent is another one shaped like a dragon – 6 – with a stinger, moustaches, branching horns, eight limbs and an eight-peaked mountain range on its back. According to the shaman Savely, this “by way of contrast, is America”. To the east of our mainland lies Sakhalin – 7 – a salmon with a seven-peaked mountain range on its back, half dark blue, half red. The mountain ranges on the backs of the dragon (America) and the fish (Sakhalin) are not shown on the ‘map’. In the upper world, above our earth and to the north of it, is the lunar world – 8 – depicted on the map to the top right of the moose. In the eastern part of the lunar world, two seas are positioned in close proximity. One of them – 9 – is the bear sea. A bear river – 10 – flows into it, itself flowing out of a lake – 11. Three small rivers flow into this lake at the same point – 12, 13 and 14. In the area around the upper reaches of these rivers there is a large lake – 15 – with an elongated form. To the east there is a special icy place not marked on the ‘map’. To the west (the upper left on the ‘map’) is a place of coals, a deposit of charcoal – 16. The second of the two adjacent seas is the tiger sea – 17. The tiger river – 18 – flows into this, having several tributaries, by whose upper reaches lies a large lake with an elongated shape – 19 – much the same as the one in the bears’ half of the lunar world. To the east of this was also a place of coals – 20. In the western part of the lunar world, between the large lakes was the moon itself, which took the form of a gleaming disc with an almost opaque cover of equal size. This cover is connected to the lunar disc by an axis lying on the circumferences of both discs. The lunar disc is immobile, and the disk-cover is constantly rotating slowly on its axis, resulting in the ever-changing phases of the moon. The moon is not drawn on the ’map’. On the bears’ half of the lunar world lives the ‘old woman’ (wife) of the master of the bears – 21; while on the tigers’ half of the lunar world there lives the ‘old woman’ of the master of the tigers – 22. We will discuss these below. The ‘masters’ of bears and tigers themselves appear to the Oroch as anthropomorphic beings. All the bears and tigers living in our world are their dogs. Above our world, to the south of it (the upper left part of the ‘map’), there is the solar world – 23, through which a river – 24 – flows with a large number of tributaries. The solar world is home to the sun maiden – 25 – with a dazzlingly bright face. The sun that we see is her face. In the northern side of the universe is a cold, icy sea – 26 – inhabited by its own evil spirit – 27 – a furry, one-armed, one-eyed anthropomorphic being with a pointed head. North-east of Sakhalin (on the lower righthand part of the ‘map’) there is a small flow-through lake – 28 – which plays an important role in shaping the souls of shamans. We will discuss its purpose in detail below. A river – 29 – flows into it from the north. Another river flows out of this lake and connects it with the walrus sea – 30. To the southwest (somewhat higher, to the left) is the whale sea – 31 – whose master is depicted in its centre – 32. The master of the whale sea feeds upon the fish-men that live in this sea – 33. Further to the west – 34 – is depicted the sea of the master of fish, in which all fish are born. The master of the fish himself is a large fish with a human head. This is a very evil and dangerous being. He has nine evil spirit-helpers on his back. To the northeast is the sea of the master of water – 35. In it live the master of water – 36 – and his “old woman” (wife) – 37. When the master of water catches a salmon, his wife guts it, and the scales turn into new fish. These fish then head off for the shores of the earth. This is how the Oroch explain the mass movements of salmonid fish (simy [cherry salmon], kety [chum salmon], and gorbushi [humpbacked salmon]). Between the sea of the master of water and the sea of whales is another small sea – 38 – which serves as the afterlife for drowned people. Directly above the earth (on the very top of the ‘map’) is a special monkey heaven. Unusually evil winged monkeys – 39 – dwell here – the spirits of black pox. There are a number of constellations on the same level as the lunar and solar worlds. Ursa Major [the Plough, or Big Dipper] is depicted on the ‘map’ below and slightly to the right of the lunar world, but as a constellation of four stars – 40. This is the hide of a huge bear, the same as that drawn in the lower right-hand corner of the ‘map’, having been slain by the supreme heavenly deity – the creator of the universe, named Khadau, to be discussed further on. This hide has been pinned out with four stakes to dry it out. The Oroch also have another interpretation of the ‘Great Bear’ that included all eight stars in this constellation. According to the second interpretation, it is a storehouse raised up on four stilts, into which a bear has climbed. The weight of the bear has caused one of the four pillars to buckle. Three hunters are creeping up on the structure: an older brother, a younger brother with a dog, and a stranger. Another constellation is depicted to the left of the lunar world, made up of ten stars arranged in an irregular oval – 42. Further to the left again is the constellation of Orion – 43 – and then the Pleiades – a constellation of seven stars that the Oroch call ‘The Seven Maidens’ – 44. These are Oroch girls taken up into heaven by the very same Khadau. A single star – 45 – located even further to the left, is apparently Venus. At the very edge of this chain of constellations, Ursa Major is depicted once again, including all eight stars. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the first four stars here depict not Ursa Major, but some other constellation. The whole ‘universe’ is enclosed in a spherical casing (the celestial sphere), which is depicted on the ‘map’ by means of two parallel lines encompassing the ‘universe’. The inner surface of this sphere is hard and blue in colour. This is the visible sky. The outer surface of the sphere is soft, like cotton wool. It is referred to as the “lid of heaven”. Above the earth itself there is a small round celestial opening in this sphere – 46. We can see this: it is the Pole Star. To the south of our world is another opening in the celestial sphere – 47 – which is called the ‘mouth of heaven’. This comprises two rows of pointed rocks facing each other, nine in each row. Both rows are locked in continuous horizontal movement to right and left, but going in different directions, in much the same way as the blades move in a hair clipper. On the outer surface of the earthly sphere, not far from the ‘heavenly mouth’, there grows an iron tree – 48 – with three branches (inadvertently depicted upside down on the ‘map’). This is the tree of the mythical iron bird ‘kori’ – 49 – which is depicted beside it. Its nose is an ice pick, the tips of its wings are sabres, its tail is a spear for hunting bears.” minimize

The Ewenki cosmological maps collected by A.F. Anisimov (1958, book available online here) are well known. For example, one of them, authored by the Ewenki shaman Vasily Sharemiktal, aided by the shamaness Katerina Pankagir, illustrates how the deceased are led off into the world of the dead – buni (Figure 6). The map depicts in detail the entire path along the mythological river that connects the various different worlds, starting from a campsite in the middle world, inhabited by people and animals, and ending in the world of the dead. The map presents a variety of zoomorphic spirit-helpers of the shaman, the inhabitants of the various shamanic worlds, and the spirits of the dead engaged in assorted economic activities.

Fig. 6. Map depicting the path to “buni”, the world of the dead. Authors: V. Sharemiktal and K. Pankagir (Anisimov 1958: 61).

The following Ewenki cosmological map from the archival collection of the Soviet scholar V.A. Tugolukov also contains the concept of a central river connecting the worlds (the River Yane) (Figure 7). This map was drawn on the island of Sakhalin by the famous Ewenki artist Semyon Nadein. Five realms are shown on the map: the Upper World (11), Middle World (1), Lower World (9 and 10), and the Worlds of Dolbor (18) and Buldyar (7), in the form of seven islands. On this map, the Upper World is shaped like a chum or deerskin tent, above which are the constellations. In the land of Buldyar there live people who look like Ewenkis. They take their wives from the Middle World. The Lower World and that of Dolbor are inhabited by non-human beings. The only hydronym on this map is the River Yane, which means “river” in Ewenki and often serves as the name of a main river.

Fig. 7. Cosmological map by Semyon Nadein, received by V.A. Tugolukov (1966, archive of the IEA RAS, collection 44, inventory 4, document 1617).

Summing up, it may be noted that virtually all the peoples of Siberia were acquainted with some forms and methods of mapping that differed in some way from Western cartography and Western ways of conceptualizing space. Toponyms also acted as a kind of “map” of a given area, enabling indigenous people to navigate in space and transmit spatial information both orally and by means of cartographic methods. The scientific study of indigenous cartography with toponymy emerged in conjunction with researchers’ growing interest in the maps of indigenous peoples, as used by travellers during their expeditions in Siberia. Scholars and travellers often added the names of places to these hand-drawn maps, as heard from the mouths of their guides. As Adler (1910: 133) put it in reference to a certain Yakut map of an area: “Comparison of this excellent map with a hundred-verst [c. 110 km] map yielded the following results: the fidelity of the relationship between individual rivers, particularly at their headwaters and watersheds, is amazing. […]. The abundance of distinct names for each tributary, channel, mountain, lake, campsite, etc. indicates a detailed knowledge of the area. This map could do honour to any European cartographer.” A significant corpus of indigenous toponyms has thus been collected in this way, and has yet to be explored in more detail with regard to its relevance to the members of indigenous peoples living today.

More information on various studies into indigenous cartography and toponymy can be found in the Resources section.

A description of the project materials can be found here.

Literature:

Okladnikova, E., “Traditional cartography in Arctic and Subarctic Eurasia”, in D. Woodward & G.M. Lewis (Eds.), Cartography in the traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific societies, vol. 2, book 3, pp. 329-349 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Shirokogoroff, S.M, Psychomental complex of the Tungus (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, 1935). The book can be read online, in Russian and English, here.

Avrorin, V.A. and Kozminsky, I.N., “Predstavleniya orochei o vselennoi, o pereselenii dush I puteshestviyakh shamanov, izobrazhenye na ‘karte’” [Oroch concepts about the universe, about the transmigration of souls and the travels of shamans as depicted on “maps”], in Sbornik muzeya antropologii i etnografii [Collection of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography], vol. 11 (Moscow-Leningrad, 1949).

Adler, B.F., Karty pervobytnykh narodov [The maps of primitive peoples] (Saint Petersburg: Tipografiya A. G. Rozen, 1910). The book is available online.

Anisimov, A.F., Religiya evenkov v istoriko-geneticheskom izuchenii i problemy proiskhozhdeniya pervobytnykh verovanii [The religion of the Ewenkis in a historical and genetic study and problems concerning the origins of primitive beliefs] (Moscow-Leningrad: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1958). The book is available online.

Vasilevich, G.M., “Drevneishiye geograficheskiye predstavleniya evenkov i risunki kart” [The oldest geographical representations of the Ewenkis and drawings of maps], in Izvestiya Vsesoyuznogo geograficheskogo obshchestva [Bulletin of the All-Union Geographical Society], No. 4, 1963, pp. 306-319.

Vakhtin, N.B., Yukagirskiye tosy [Yukagir tosy] (Saint Petersburg: European University Press, 2021).

Jochelson, V.I., Po rekam Yasachnoi i Korkodonu. Drevny i sovremenny yukagirsky byt i pis’mena [Along the Yasachnaya and Korkodon Rivers. Ancient and modern Yukagir life and writings] (Saint Petersburg, 1898).