The live toponymic platform consists of three components: the Ewenki toponymic database, the GIS platform itself, and the website.

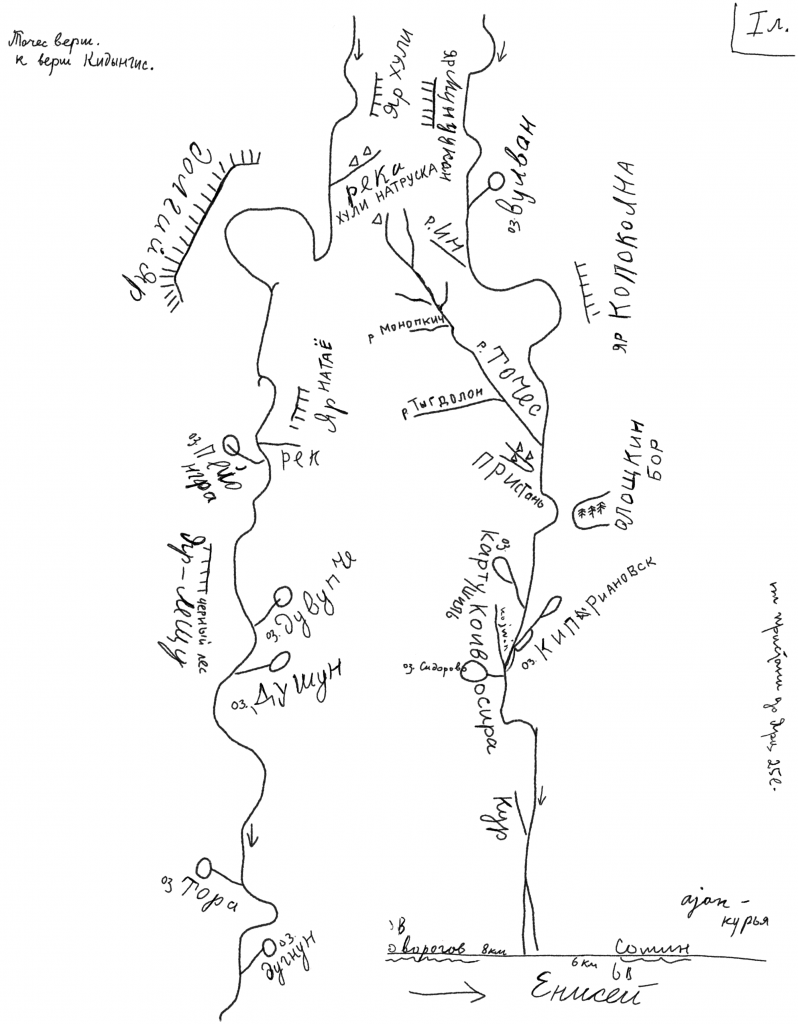

The Ewenki toponymic database contains place-names from both archival sources and those collected by researchers in Ewenki settlements in Khabarovsk Territory (2017), Yakutia (2018), Transbaikalia and Amur Region (2021). Most toponyms from archival sources are taken from hand-drawn maps made by the outstanding Soviet Tungusologist Glafira Makaryevna Vasilevich. These maps were kept for many years at the Siberian Department of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Saint Petersburg and have only recently been transferred to the scientific archive of the MAE RAS and catalogued. The archive contains thirty hand-drawn maps collected by Vasilevich among the Ewenkis in several regions of Siberia from the 1920s to the 1960s, as well as several travel maps that the researcher used during her field work, and various other cartographic materials. G.M. Vasilevich herself published only four maps during her lifetime. All the maps depict river systems and feature around 1,500 toponyms.

Example map (image redrawn from a Vasilevich map in the archive of the MAE RAS, Vasilevich collection 22, inventory 2, file 75, sheet 6):

The greater part of the names recorded by Vasilevich are river names or hydronyms.

In our research work, we:

- Compiled a unified list of the place-names found in Vasilevich’s archival maps.

- Identified which river systems they belong to and mapped them (see Map 1).

- Translated a significant part of the toponyms into Russian using the available dictionaries and published ethnographic materials, subsequently discussing and refining these translations with native speakers in the settlement of Iengra, Yakutia (N.A. Mamontova).

- Conducted a comparative study to ascertain the degree of preservation and variability of the place-names concerned.

Map 1. Geolocation of the toponyms from G.M. Vasilevich’s archived maps

Further work involved the integration of the archival materials into the GIS platform. Work on the geolocation of the river names was complicated by the fact that a number of the maps in the archive have no information as to where and when they were made, and most of the rivers are either absent from official maps or appear under other names. Future work on the scientific legacy of Vasilevich should shed more light on her cartographic project and the specifics of how she worked with her research participants. At the present stage, we have identified the largest rivers whose modern names match those on the archival maps, which should enable us to link the hand-drawn maps with specific geographical features in the form of a polygon (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. An example of how one of Vasilevich’s archival maps was integrated into the GIS platform.

This problem may be termed “the map point problem”, referring to situations where it is not possible to accurately pinpoint an object on the map due to its small size, or where the name reflects a spatial relationship between several objects rather than a specific geographical object, as well as relationships between geographical features, people, animals and the spirits associated with a particular place.

The “map point problem”

- Many place-names are not visible on GIS maps.

- Archival maps lack exact references to a given place.

- Schematic maps and other non-standard cartographic media.

- Indigenous forms of cartography (maps without maps / narrative as an example of oral “mapmaking”).

The solution in this case was to opt for mixed forms of mapping, combining hand-drawn maps, GIS information and any other data not associated with the standard forms of representation (see Fig. 2). The latter include, for example:

- Mythological narratives (e.g. how the trickster hero gave names to places)

- Associations with the spirits of the ancestors.

- Hunting stories and interrelations with game animals.

- Narratives explaining the origins of named objects or how their names came about.

- Stories and commentary revealing what activities people actually engage in at the places named.

Fig. 2. An example of the connections between narratives about the guardian spirit of a territory and the name of the place on the GIS platform.

The next task that had to be solved in the project was that of how to display several different place-names for one and the same object on the map.

Place-names as assemblages / Multi-layeredness

Multi-layered simultaneity (Blommaert 2018) arises when several chronotopes or spatio-temporal configurations are synchronized in such a way as to form a new chronotope that is more suitable for the present moment. In other words, place-names should be associated with a particular experience, story, myth, practice, or landscape. It can happen that even in the same community a name can take on additional meaning depending on the individual experience of a group of people, such as a nomadic family unit or a group of hunters (see Figure 3). If the connection between the object and its name is ruptured, the name of the place may change completely, or else the object can temporarily be left without any name whatsoever. This sort of thing occurs, for example, when a radical change takes place in the landscape or the in kinds of economic activity pursued in a given location.

Fig. 3. An example of the multi-layeredness of a place-name in the GIS platform.

Changes in the landscape are often associated with a variability in the semantics of names given to landscape features, when one and the same term is used to denote different geographical objects. Since many toponyms directly designate geographical objects, it is important to record data not only about the name of a place, but also about the semantics of the term used to denote a particular geographical feature. This aspect is discussed in more detail in the section on methodological recommendations, provided as an aid to researchers and community members collecting toponymic information.

More information on the project and the GIS platform can be found here.